The Roman Empire grew to its peak around what is now known as the reign of the “five good emperors” – Nerva Reign (A.D. 96-98), Trajan Reign (A.D. 98-117), Hadrian Reign (A.D.117-138), Antoninus Pius Reign (A.D. 138-161), and Marcus Aurelius Reign (A.D. 161-18). 1

After that, the Roman Empire started to slide downhill with internal political strife due to military despotism and wars against the tides of foreign enemies – the Persians in Asia, the Goths in the East, and the Franks and Alemanni (Germanic tribes) in the West – “not wars for the sake of conquest and glory as in the time of the republic, but wars of defense and for the sake of existence.”2

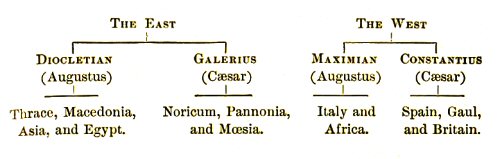

When Diocletian ascended as Emperor in A.D.284, he “saw that it was difficult for one man alone to manage all the affairs of a great empire. It was sufficient for one man to rule over the East, and to repel the Persians. It needed another to take care of the West and to drive back the German invaders.”3 He promoted his trusted general, Maximian to take care of the Western region of the Roman Empire. In time, Diocletian decided the two chief rulers of the Eastern and Western Roman Empire, given the title of Augustus, further needed an assistant each who were given the title of Caesar. Under Diocletian’s tetrarchy, the two Caesars, Galerius and Constantius, were regarded “as the sons and successors of the chief rulers, the Augusti. Each Caesar was to recognize the authority of his chief; and all were to be subject to the supreme authority of Diocletian himself. The Roman world was divided among the four rulers as follows: 4

Diocletian’s tetrarchy was set up with the aim of avoiding succession strife within the Roman Empire that had plagued and weakened the Empire during what was now known as the Crisis of the Third Century (A.D. 235 – 284). Little did he know that this set the stage for the Western and Eastern Roman Empire to become “more and more separated from each other, until they became at least two distinct worlds, having different destinies.”5

Diocletian’s tetrarchy was set up with the aim of avoiding succession strife within the Roman Empire that had plagued and weakened the Empire during what was now known as the Crisis of the Third Century (A.D. 235 – 284). Little did he know that this set the stage for the Western and Eastern Roman Empire to become “more and more separated from each other, until they became at least two distinct worlds, having different destinies.”5

Beside the tetrarchy system, Diocletian was also responsible for the last and most sever persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire under the incitement of Galerius on February 24, 303. 6 Despite what would be later termed as the Diocletianic Persecution, 7 “nearly one-third of Rome was Christian when Constantine the Great converted in 312. 8 After a series of civil wars which Diocletian’s tetracrchy model inevitably resulted, Constantine rose to power as sole ruler of both Western and Eastern Roman Empire and “founded a “New Rome” in the East in 324 on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium and called it Constantinople in honor of himself.” 9 When Rome was sacked in 410, the Roman Empire became permanently divided with an Emperor of the West ruling from Milan then Ravenna, and an Emperor of the East from Constantinople. 10

The arts enjoyed more freedom from the polytheistic cultures of Greece and Rome antiquity. “With the adoption of Christianity, first as an option then in effect as the official religion, Constantine ended this freedom. Henceforth, devotion was focused on a monotheistic god … from the very start, Constantine adopted Christianity as a spiritual and social aid to central government. It rapidly became a state religion, and more than that: Church and state formed a seamless garment, which the population wore whether they liked it or not.” 11

Amidst this transitional backdrop from a persecuted faith to a faith elevated as state religion, Christianity went through a great change with the influx of believers, of which many were forced into the faith who bring their old pagan practices and amalgamated with the original Christian practices. Though Christian iconography existed before Constantine, Byzantium iconography rose in popularity during this transitional period to the dilemma of the early Christian fathers.

“Christians were deeply suspicious of the practice of imaging the divine, whether on portable panels, on the walls of churches, or especially as statues that reminded them of pagan idols. The opponents of Christian figural art had in mind the Old Testament prohibition of images the Lord dictated to Moses in the Second Commandment: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven images or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: (Exod. 20:4,5).”

When, early in the fourth century, Constantia, sister of the emperor Constantine, requested an image of Christ from Eusebius, the first great historian of the Christian Church, he rebuked her, referring to the Second Commandment:

Can it be that you have forgotten that passage in which God lays down the law that no likeness should be made of what is in heaven or in the earth beneath? … Are not such things banished and excluded from churches all over the world, and is it not common knowledge that such practices are not permitted to us … lest we appear, like idol worshippers, to carry our God around in an image?” 12

The elevation of the Christian faith to a state religion also brought about conflicts between the Christian pious against state officials despite the fact that the Church thrived under imperial patronage. Of note were the consistent frictions between Archbishop of Constantinople John Chrysostom and Eudoxia, wife of Emperor Arcadius during Arcadius’ reign (395-408). Sozomen, a Christian Church historian, highlighted that their rivalry stems from an ornate statue made in honor of Eudoxia which Chrysostom condemned:

“The silver statue of the empress … was placed upon a column of porphyry; and the event was celebrated by loud acclamations, dancing, games, and other manifestations of public rejoicing … John declared that these proceedings reflected dishonor on the church.” 13

Jean-Paul Laurens, Saint John Chrysostom and Empress Eudoxia, 1880, oil on canvas, (could not find the size data)

Jean-Paul Laurens, Saint John Chrysostom and Empress Eudoxia, 1880, oil on canvas, (could not find the size data)

Eudoxia’s son Theodosius II was made Emperor of Eastern Roman Empire at age seven. When Theodosius II was thirteen, his sister, Aelia Pulcheria proclaimed herself regent over him at the age of fifteen on July 4, 414, making herself Augusta and Empress of the Eastern Roman Empire. According to Sozomen, Pulcheria took a vow of virginity when she became Augusta. Pulcheria was to play a pivotal role in Church History by presiding and guiding the Council of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), which promoted the Marian title of “Theotokos,” – “the one who gives birth to the one who is God” or “Mother of God.”

For the Byzantium Art History assignment, we were tasked to pair up with a classmate to do portraits of each other in accordance to the Byzantine conventions. Being a Catholic (practising but by no means devout), I immediately wanted to do a portrait based on the Byzantium Theotokos canon. As there were only two female classmates in the cohort and one of them did not seem interested in being portrayed in a Mary-like image, I quickly approached Heather to be my partner for the Byzantium project.

Heather kindly accept my request and we exchanged photos of each other to work on the project. I made it known to her that I am planning to use the Theotokos of Vladimir as my primary canon and Heather took photos of herself that emulated that pose in particular, even with a hoodie in place of a head veil, which was very helpful. We discussed what kind of personal characteristic we wanted to include in our art pieces and decided to use the game “Portal 2” as a common thread which link both of our art pieces. My first contact with Heather was through emails with regards to my switching modules to a 3D rigging class, which she was already in, during the first week of Fall semester. She was very generous and kind in helping me get up to speed after missing the first rigging lesson. We are the only two MFA students taking the 3D rigging class in the Fall 15 semester. Thus we felt that we could stress this shared personality trait in our art works without getting too personal. Heather suggested using elements from the 3D game “Portal 2” (which was created by Kim Swift, a DigiPen Alumni, who also did Portal) to show our DigiPen lineage and to reflect our present 3D rigging student background. With the above, I established a mood board to work with as follows:

Sen Lieh Kiew, Mood board with Theotokos of Vladimir, Heather Smith Photos, and Valve – Portal 2 elements, October 19, 2015, Adobe Photoshop 1920 X 1080 pixels at 72 dpi.

Sen Lieh Kiew, Mood board with Theotokos of Vladimir, Heather Smith Photos, and Valve – Portal 2 elements, October 19, 2015, Adobe Photoshop 1920 X 1080 pixels at 72 dpi.

Serendipitously, Theotokos of Vladimir which is considered an archetype of the Eleus (tender affection) iconographic type of Theotokos fits Heather’s gentle, kind and soft-speaking personality. In the Eleus Theotokos type, the child Christ snuggles up to his mother’s cheek, embraces her with his left hand, while Mary holds Christ with her right hand while leaning her head towards him. Also, Christ characteristically bends his left leg in way that his left heel can be seen.

Unknown icon painter, Theotokos of Vladimir, early 12th century, tempura on panel, approximately 41″X 27″.

Unknown icon painter, Theotokos of Vladimir, early 12th century, tempura on panel, approximately 41″X 27″.

I chose Theotokos of Vladimir because it is considered the “most Orthodox and revered icon in medieval Russia … brought from Constantinople in the early 12th century … destined to become the holy of holies of the Russian state.” 14 Also, its detail of the Virgin’s left eye and nose is part of the logo of Icon Production, founded by Mel Gibson, who directed what I personally considered the definitive Passion movie “The Passion of The Christ.” 15

However, my source material has been too ravaged by time to give me good advice on details. So I chose the following icon placed in a Greek Orthodox Cathedral website for detailing reference.

Unknown icon. Unknown medium. Assessed on October 27, 2015. http://www.stgeorgegreenville.org/OurFaith/Feasts%20for%20Theotokos/Theotokos%20in%20Icons.html.

Unknown icon. Unknown medium. Assessed on October 27, 2015. http://www.stgeorgegreenville.org/OurFaith/Feasts%20for%20Theotokos/Theotokos%20in%20Icons.html.

I tried tracing the origin of the above image, but could not find anything to give it proper captioning. But considering that it is an image placed on an Orthodox Cathedral website, I wager that it is not totally against the Byzantium type.

In Byzantium iconography, it is a tradition to copy from a source material as closely as possible to link back to the historical person portrayed. The Theotokos of Vladimir, like many other icons, is believed to have some linkage to an original image painted by Saint Luke from its living subjects. As such, I decided that I have to trace the silhouette and some features (the eyes and hands) of the Theotokos of Vladimir to inject authenticity.

Sen Lieh Kiew, Tracing of Theotokos of Vladimir process, October 23, 2015, Adobe Photoshop 1920 X 1080 pixels at 72 dpi.

Sen Lieh Kiew, Tracing of Theotokos of Vladimir process, October 23, 2015, Adobe Photoshop 1920 X 1080 pixels at 72 dpi.

The line quality of Theotokos of Vladimir is very uniform in thickness. I tried my best to have as many single continuous stroke lines to produce uniform line thickness. But you can see from above that I failed miserably. Another problem I encounter is that Heather’s sweater will not have enough logical drapery drag to produced a silhouette similar to the lower left corner of Theotokos of Vladimir. I decided to place two definitive box elements of Portal 2 behind Heather to fix the silhouette matching issue.

Sen Lieh Kiew, Fixing of Theotokos of Vladimir left bottom corner silhouette process,

Sen Lieh Kiew, Fixing of Theotokos of Vladimir left bottom corner silhouette process,

October 23, 2015, Adobe Photoshop 1920 X 1080 pixels at 72 dpi.

Color wise, there are certain constraints set by Byzantium iconography. While I was not able to find resources that describe what the colors of Byzantium iconography of antiquity means, I found a contemporary website discussing the symbolism of icon colors by an Orthodox clergy. Given the fact that Byzantium iconography is a copy of a copy of copy from an ancient original, it is likely that the contemporary symbolism stays true to the originals of antiquity. Below are some excerpts from the website which I used as canon when I did my color choices:

“Colors – whether bright or dark – were never mixed but always used pure. In Byzantium, color was considered to have the same substance as words, indeed each color had its own value and meaning. One or several colors combined together had the means to express ideas …

Gold

Gold symbolized the divine nature of God himself. This color glimmers with different nuances in the icon of the Mother of God of Vladimir.

Red

Red is the color of heat, passion, love, life and life-giving energy, and for this very reason red became the symbol of the resurrection – the victory of life over death. But at the same time it is the color of blood and torments, and the color of Christ’s sacrifice.

White

White is the symbol of the heavenly realm and God’s divine light. This is the color of cleanliness, holiness and simplicity.

Brown

Brown is the color of the bare earth, dust, and all that is transient and perishable.

Black

Black is the color of evil and death.

Colors Not Used in Iconography

A color that was never used in iconography is gray. When mixing black and white together, iniquity and righteousness, it becomes the color of vagueness, the color of the void and nonexistence. There was no place for this color in the radiant world of the icon.”16

With the color palette established tightly by Byzantium tradition, I took care to use dark blue instead of black and avoided grey for my iconography of Heather. The result is as follows:

Sen Lieh Kiew, Heather Smith of Redmond,

Sen Lieh Kiew, Heather Smith of Redmond,

November 4, 2015, Adobe Photoshop 2000 X 3134 pixels at 300 dpi.

A dark brown outline is used to imply the earthly being of Heather and P-Body (the Christ infant replacement, which is a 3D character made by perishable humans). I robed Heather in Marian blue partly because she was in a blue sweater in the photos she gave me and also to tie back to the Mary figure of the Theotokos original. I chose to use off-white for P-Body as he will be too overbearing if he is to keep to his original pure white Besides, only saints and the divine are allowed to be robed in white in Byzantium iconography canon. What appears as grey shadows on P-body is actually dull blue. I tried using cross hatching methods to describe highlights and shadows for the draperies on Heather in emulation of Byzantium model. I am sure I have broken many strict Byzantium iconography rules in this aspect, but I hope it gets the idea across that I did consider copying the unique Byzantium handling of draperies. Gold is used as background to reflect the state of divine ecstasy that Heather experiences when allowed to do 3D artworks (I may be projecting and exaggerating here). Despite possibly being off-model, I decided to use a different gold texture from the background for the halos with silver linings (the white lines are supposed to be silver linings) in order to bring variety to the piece. Heather’s skin is also painted more pinkish instead of Middle Eastern brown so that people can see it is a secular portrait of Heather done in Byzantium style. To cap it all, I placed the Greek equivalents of the first and last alphabets of Heather’s and B-Body’s name around the halo areas as is customary of Byzantium icons. I would have drawn the Greek alphabets with better font design given more time.

I am certain that I am far from staying true to Byzantium iconography canon due to my lack of Orthodox iconography training and time. But I did what I can with the knowledge I amassed in the little time that I have. I hope I did Heather justice in portraying her gentleness and love for 3D art work. I also pray that the Lord will see this as an obvious secular artwork and not a sacrilegious act with the replacement of the Christ child with P-Body.